Since 1970, the U.S. federal government has considered marijuana a schedule 1 controlled substance. This categorization, shared with drugs such as heroin and LSD, means the federal government deems marijuana to be a dangerous drug with a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical use.[1] Nonetheless, according to state laws, it is legal for adults over 21 years of age to grow, process, sell, or consume recreational marijuana in 11 states. (In the District of Columbia, voters approved a measure to legalize, but federal law prohibits implementation.)[2] Furthermore, a total of 33 states and the District of Columbia allow medical marijuana sales and consumption.[3]

Nevertheless, marijuana is an addictive product with certain societal costs, which means that states with legalized marijuana sales desire some control over the market. This control is maintained through a regulatory system as well as excise taxes.

This paper focuses on the design of the excise taxes on recreational marijuana. Medical marijuana should not be subject to excise taxes to the extent that it is genuinely consumed for medical reasons. While recreational marijuana shares negative externalities (secondhand smoke, driving under the influence, health impacts) with other “sinful” products like tobacco and alcohol, medical marijuana would by definition not be viewed the same way when recommended as a treatment for medical conditions.[4] The case for or against marijuana legalization is outside the scope of this paper. Rather, our focus is to help policymakers consider appropriate tax regimes to the extent that they decide to legalize the product for recreational use.

Legalization of recreational marijuana is a still relatively new trend, but diminishing tax receipts from traditional sources of revenue as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, reports of growing marijuana sales, and popular support make it likely that more states (and maybe the federal government) will consider legalizing and taxing marijuana.[5] However, excise taxes should, as a guiding principle, only be levied when appropriate to capture some negative externality or to create a “user pays” system—not as a general revenue measure.

Comprehensive policy recommendations are still developing because the market for recreational marijuana is rather young—in 2014, Colorado was the first state to allow sales. Analysts, businesses, and lawmakers alike are still improving their understanding of the complexities of legalization. This paper aims to contribute to the discussion surrounding recreational marijuana excise tax design. It does so by presenting arguments for a principled tax design of recreational marijuana and by discussing the different strategies and lessons from states with established marijuana markets.

The first section presents the marijuana market data and tax design from U.S. states. The second section discusses tax design options for states and the federal government as well as some of the factors impacting tax policy design in the marijuana space.

The marijuana plant, like any plant, is made up of several components. Each component has different qualities and potency defined by content of cannabinoids. Researchers believe there may be more than a hundred different cannabinoids or chemicals present in cannabis.[6] Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the main psychoactive compound and is generally used to define potency of the marijuana product even though there are other compounds in the plant which may influence the effects on the user. The plant is sold in different stages of development depending on the intended use by the consumer.

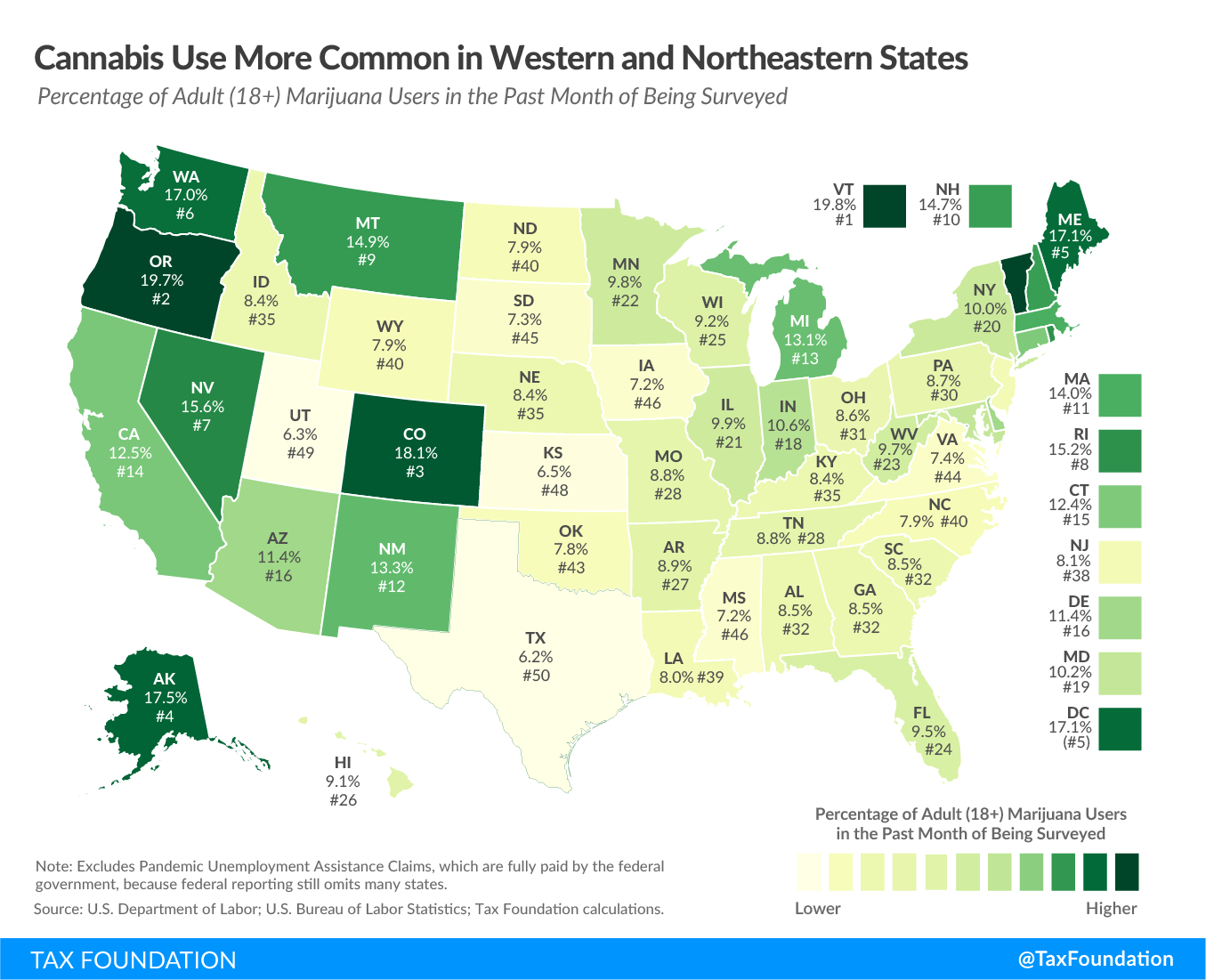

A significant part of the U.S. population lives in jurisdictions that allow marijuana consumption—medical or recreational. Legal recreational marijuana sales are ongoing in nine states, covering 27 percent of the U.S. population, but if you include medical marijuana the statistic jumps to 69 percent. According to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), in 2018, 10.5 percent of adult Americans (25.2 million) had used marijuana products in the last 30 days.[7] The marijuana market size in the U.S. is approximately 26 million pounds.[8]

While there is a rather large group of Americans that use marijuana products on a regular basis, it is an important consideration that the vast majority of marijuana products is consumed by heavy users. In fact, data from Colorado suggests that more than 70 percent is consumed by people using the product more than 26 days a month.[9] This point is important to remember when designing excise taxes as this group will pay most of the taxes, which in turn can increase the regressive effects of high excise taxes on marijuana. A similar characteristic is seen with alcohol consumption.

Another development with implications for tax design is the increasing THC content in marijuana products. According to one study, THC content grew from an average of 4 percent in 1995 to an average of 12 percent in 2014.[10] While this development predates legalization, there is, according to data from one state, no evidence that legalization does anything to reverse the trend. On the contrary, in Colorado, THC content in both marijuana flower and trim has increased significantly since legalization.[11]

Legalization has had an effect on the type of products consumers purchase. In Colorado, since legalization, flower’s share of the market has decreased from 69 percent to 43 percent. Growing categories include concentrates and edibles—a development expected to continue.[12]

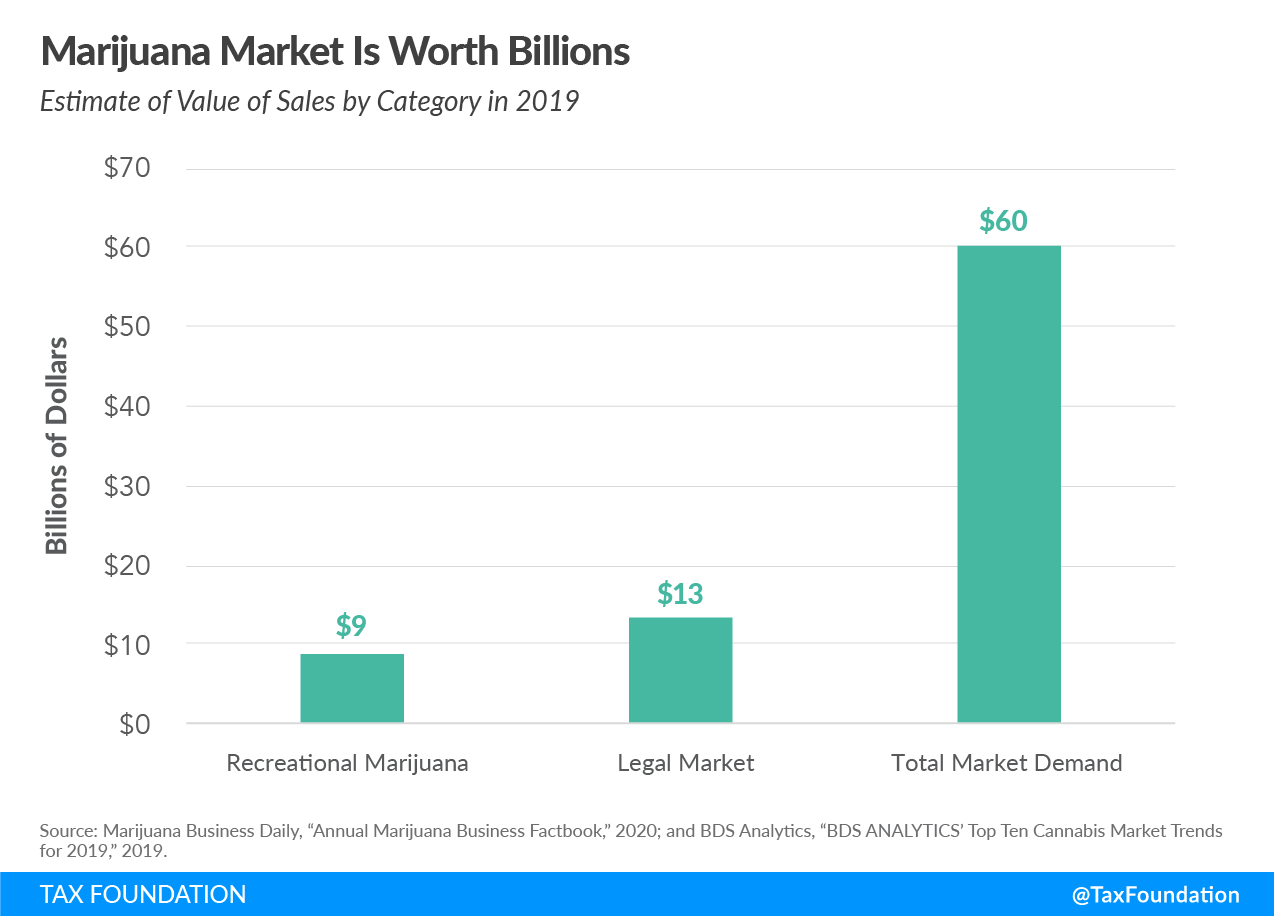

A large group of consumers results in a valuable market. Estimates suggest that the legal marijuana market was worth between $11.0 billion and $13.7 billion in 2019, and may be worth up to $30 billion by 2023.[13] If these projections materialize, the value of marijuana sales will grow to two times that of firearms and ammunition, and three times that of McDonald’s sales revenue in the U.S (2018 data).[14] In 2019, recreational marijuana was estimated to make up about 60 percent of the market but is expected to grow to closer to 75 percent by 2023.[15]

The above figures relate only to the legal market, but estimates put the value of the full market—including marijuana currently traded illegally—around $60 billion.[16] By this estimate, illegal sales still make up about 78 percent of the total marijuana sales in the U.S. In other words, legal recreational marijuana is big business and is growing. If the legalization trend continues and more consumption is moved to the legal market the regulated and taxed share may become even bigger.

With these numbers in mind, from a pure tax policy perspective, there is great incentive to legalize marijuana. Bringing sales worth $60 billion into the legal arena represents a significant opportunity for new revenue for states. While excise taxes should not be considered a tool to raise funds for general spending due to their narrow bases and distortionary effects, other taxes, like sales taxes, property taxes, and income taxes levied on newly-legal businesses can provide meaningful revenue for all levels of government.

To successfully legalize recreational marijuana, lawmakers must develop regulatory frameworks and tax structures that can compete with the illegal market. Fortunately, they do not have to start from scratch, taking note of the lessons learned in states already operating legal marijuana markets. The following sections walk through the key discoveries from states with operational markets.

States have designed different excise tax systems as they, one by one, have legalized recreational marijuana. While most states tax based on price (ad valorem), several states also tax marijuana based on weight or, in the case of Illinois, by THC content.[17] Alaska is the only state which currently taxes solely based on weight. In total, states were projected to collect $1.8 billion in excise tax revenues on marijuana in 2020, though these estimates predated the COVID-19 pandemic.[18]

Alaska

$50/oz. mature flower; $25/oz. immature flower; $15/oz. trim; $1 per clone

California

15% retail excise tax; $9.65/oz. flower; $2.87/oz. leaves cultivation tax; $1.35/oz cannabis plant

Colorado

15% excise tax (levied at wholesale by weight at average market rate); 15% excise tax (retail price)

Illinois

Potency (ad valorem)

7% excise tax of value at wholesale level; 10% tax on cannabis flower or products with less than 35% THC; 20% tax on products infused with cannabis, such as edible products; 25% tax on any product with a THC concentration higher than 35%

Maine (a)

10% excise tax (retail price); $335/lb. flower; $94/lb. trim; $1.50 per immature plant or seedling; $0.30 per seed

Massachusetts

10.75% excise tax (retail price)

Michigan

10% excise tax (retail price)

Nevada

15% excise tax (levied at wholesale by weight at Fair Market Value); 10% excise tax (retail price)

Oregon

17% excise tax (retail price)

Vermont (b)

Washington

37% excise tax (retail price)

(a) Maine legalized recreational marijuana in November 2016 by ballot initiative. The state is slated to implement a legal market later in 2020.

(b) Vermont legislators passed legalization of recreational marijuana in January 2018. The process to establish regulated sales are ongoing.

District of Columbia voters approved legalization and purchase of marijuana in 2014 but federal law prohibits any action to implement it. In 2018, the New Hampshire legislature voted to legalize the possession and growing of marijuana, but sales are not permitted. Alabama, Connecticut, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Tennessee impose a controlled substance tax on the purchase of illegal products (the tax is normally levied on a person in possession of controlled substances).[19] Several states allow local taxes as well as general sales taxes on marijuana products. Those are not included here.

Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax.

In addition to levying excise taxes, most states also levy the state general sales tax A sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. on recreational marijuana. The exceptions are Alaska, Colorado, and Oregon; Alaska and Oregon do not have a statewide sales tax.[20]

Levying sales taxes on recreational marijuana products should be encouraged. A well-designed sales tax is levied on all final consumer goods and services while exempting all purchases made by businesses that will be used as inputs in the production process.

Retail sales began in Alaska in October 2016 after voters in November 2014 approved Ballot Measure 2 legalizing marijuana (53 percent to 47 percent).[21] Alaska is the only state with a purely specific marijuana tax structure, taxing at $50 per ounce of mature flower, $25 per ounce of immature flower, $15 per ounce of trim, and $1 per clone.

Levying a specific excise tax guarantees a higher level of stability for tax collectors and is both more neutral and simpler than ad valorem taxation. However, it can create pressure on businesses as the tax rate acts as a price floor. In Alaska, cultivators have grown worried about their margins, as falling prices do not result in lower taxes; rather, as a percentage of price, falling prices result in a tax increase. When operations began in 2016, the excise rate of $50 per ounce equaled a 20 percent tax of the average wholesale price of $250 per ounce. In 2019, the price had adjusted to roughly $145 per ounce, effectively raising the rate to 35 percent; prices have since increased again.[22]

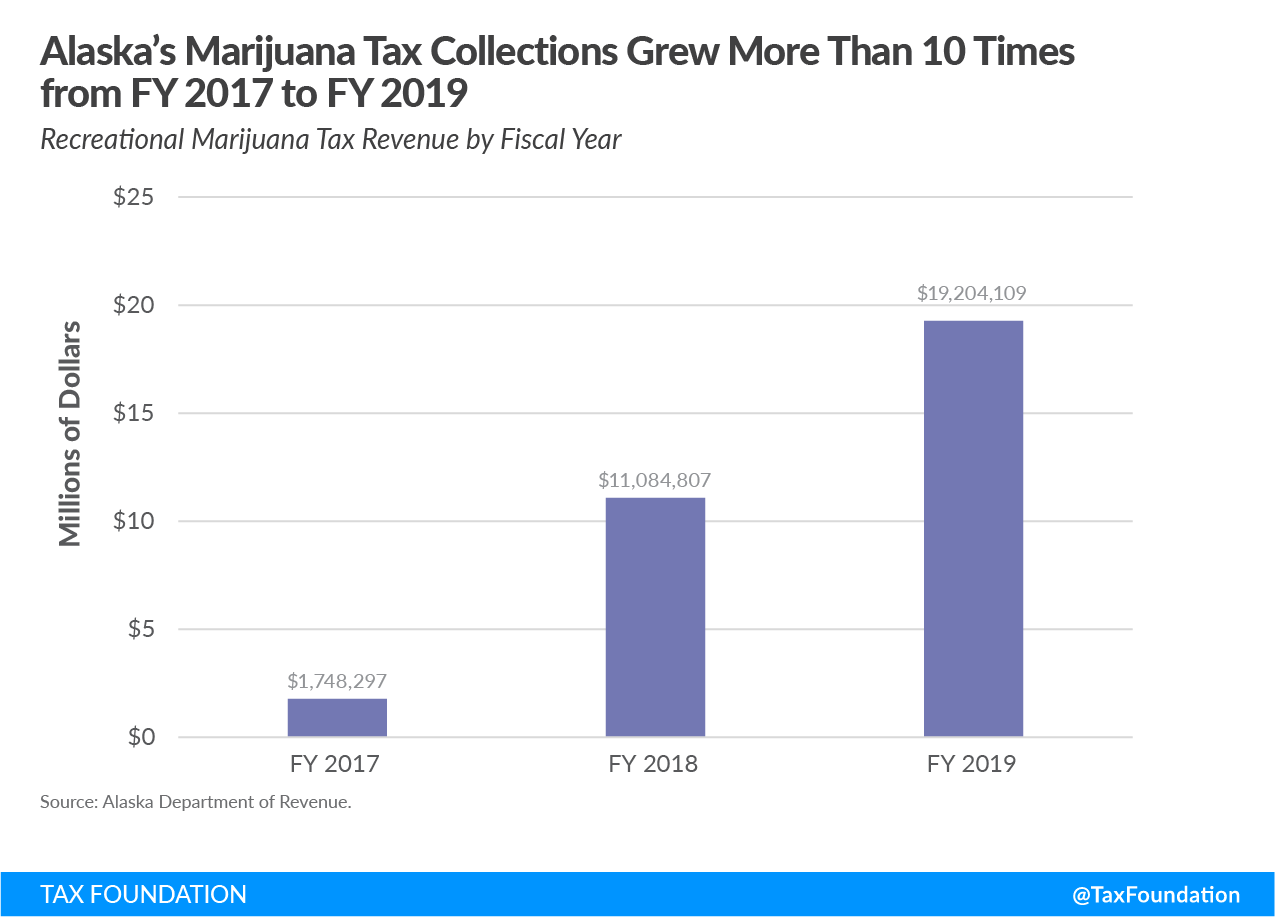

Alaska’s Department of Revenue estimated state tax marijuana revenue between $5.1 million and $19.2 million per year, with regulatory and enforcement costs between $3.7 million and $7 million.[23] In FY 2019, Alaska met its original projections as the state collected $19.2 million after 173 percent revenue growth compared to FY 2018.[24]

Alaska is on track to increase revenue collections in FY 2020. Revenue collected in Alaska is allocated as follows: 25 percent to the general fund; 50 percent to the Department of Public Safety, Health and Social Services, and Department of Corrections; and 25 percent to the Marijuana Education Fund. The latter fund pays for educational services related to marijuana use.

California voters approved (57 percent to 43 percent) Proposition 64 on Election Day in 2016,[25] and sales started in January 2018. At the state level, recreational marijuana is taxed in a mixed system: sales are taxed at 15 percent of value at retail, and cultivation is taxed at $9.65 per ounce for flower, $2.87 per ounce for leaves, and $1.35 per ounce for fresh cannabis plants (a category added post-Proposition 64 by regulatory authority). The specific rates on wholesale are indexed to inflation Inflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. .[26] In addition, the state levies the general sales tax.

One curious detail about the system is that the retail value tax is levied at the wholesale level. For this reason, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (CDTFA) has to calculate an Average Market Price (AMP) value, which it does by marking up the wholesale value by 80 percent. This means that marijuana worth $100 at wholesale will be taxed at 15 percent at the AMP value of $180.[27] This collection system has generated significant criticism in California. The markup rate increased as of January 2020 by virtue of inflationary adjustment; many believe taxes were already too high to compete with the illicit market.[28]

Furthermore, the cultivation tax is currently levied on the final distributor rather than the first. California Governor Gavin Newsom (D) has supported simplifying marijuana tax administration by collecting retail tax at the retail level and cultivation tax from the first distributor but has postponed the process to 2021 due to the coronavirus outbreak.[29]

Localities in California generally levy additional taxes per square foot on cultivation through gross receipts taxes—a practice that should be avoided. Gross receipts taxes result in tax pyramiding, meaning that taxes are added at each level through the value chain.[30]

California is the world’s largest market for recreational marijuana with legal sales totaling approximately $3.1 billion in 2019. However, legalization has not yet overcome the well-established illicit market, which is estimated to still control 74 percent ($8.7 billion) of the total market for marijuana. In fact, the year after recreational marijuana was legalized in California, the illicit market grew,[31] likely a combination of high tax rates (above 40 percent of retail selling price) and lack of enforcement against illicit sellers. Average retail prices of marijuana products increased in California post-legalization.[32] In addition, a complicated licensing system where localities have to opt-in as well as adopt local regulation and taxes (effective rate average roughly 14 percent of retail price) has created high compliance costs for would-be entrepreneurs.[33] The opt-in system also means that about two-thirds of localities in California do not allow marijuana businesses to operate.[34]

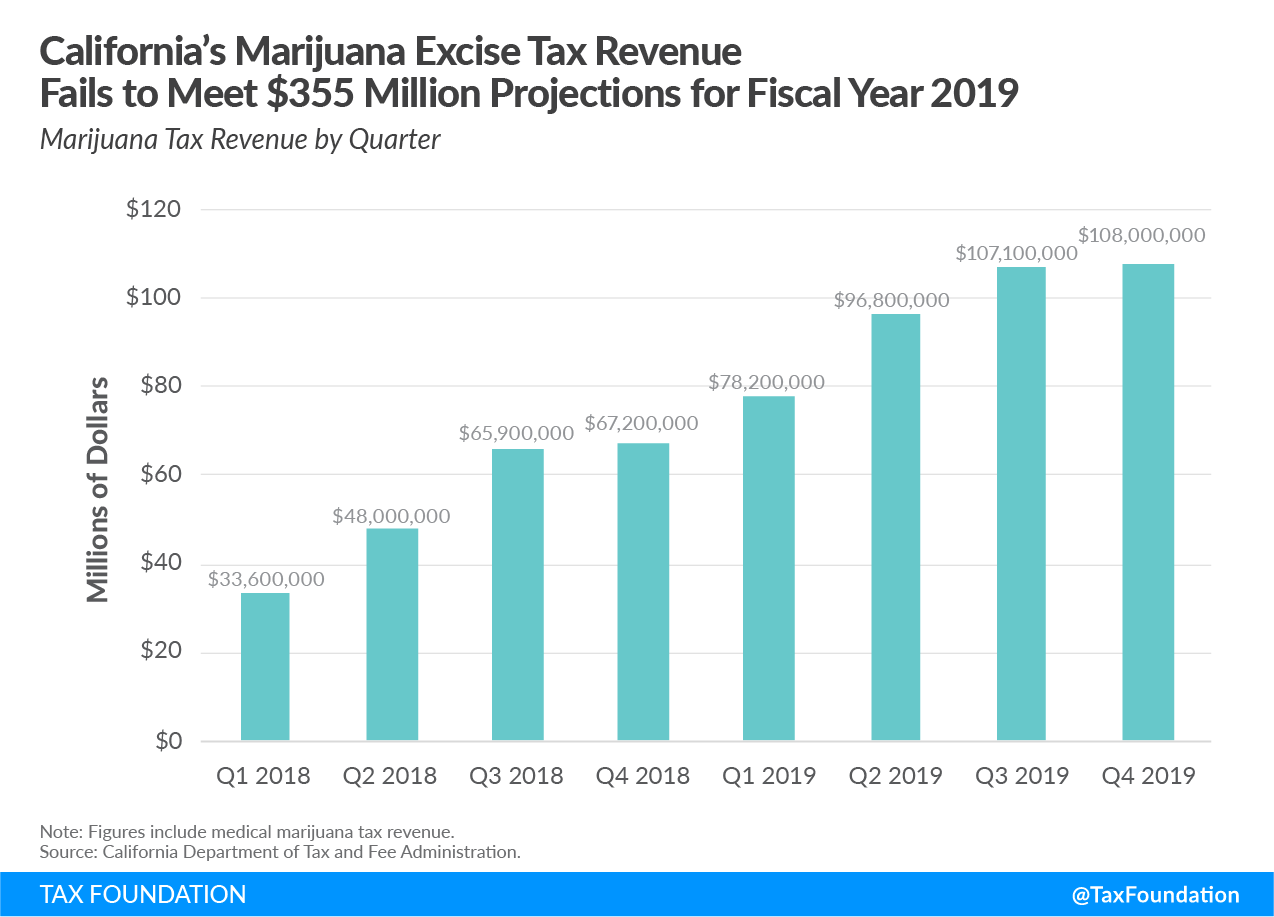

The inability to outcompete the illicit market means that excise revenue is not nearly as high as expected by many policymakers and analysts, who hoped the state could collect $1 billion each year in taxes. Governor Newsom estimated a more realistic excise revenue of $355 million for FY 2019, but California collected only $310 million that year. In Gov. Newsom’s budget for FY 2020, he projects a marijuana tax revenue of $443 in FY 2020 and $435 in FY 2021.[35]

California allocates some revenue to regulatory costs and research. After that is funded, additional revenue, approximately $200 million, goes to youth anti-drug programs (60 percent), environmental programs (20 percent), and public safety grants (20 percent).

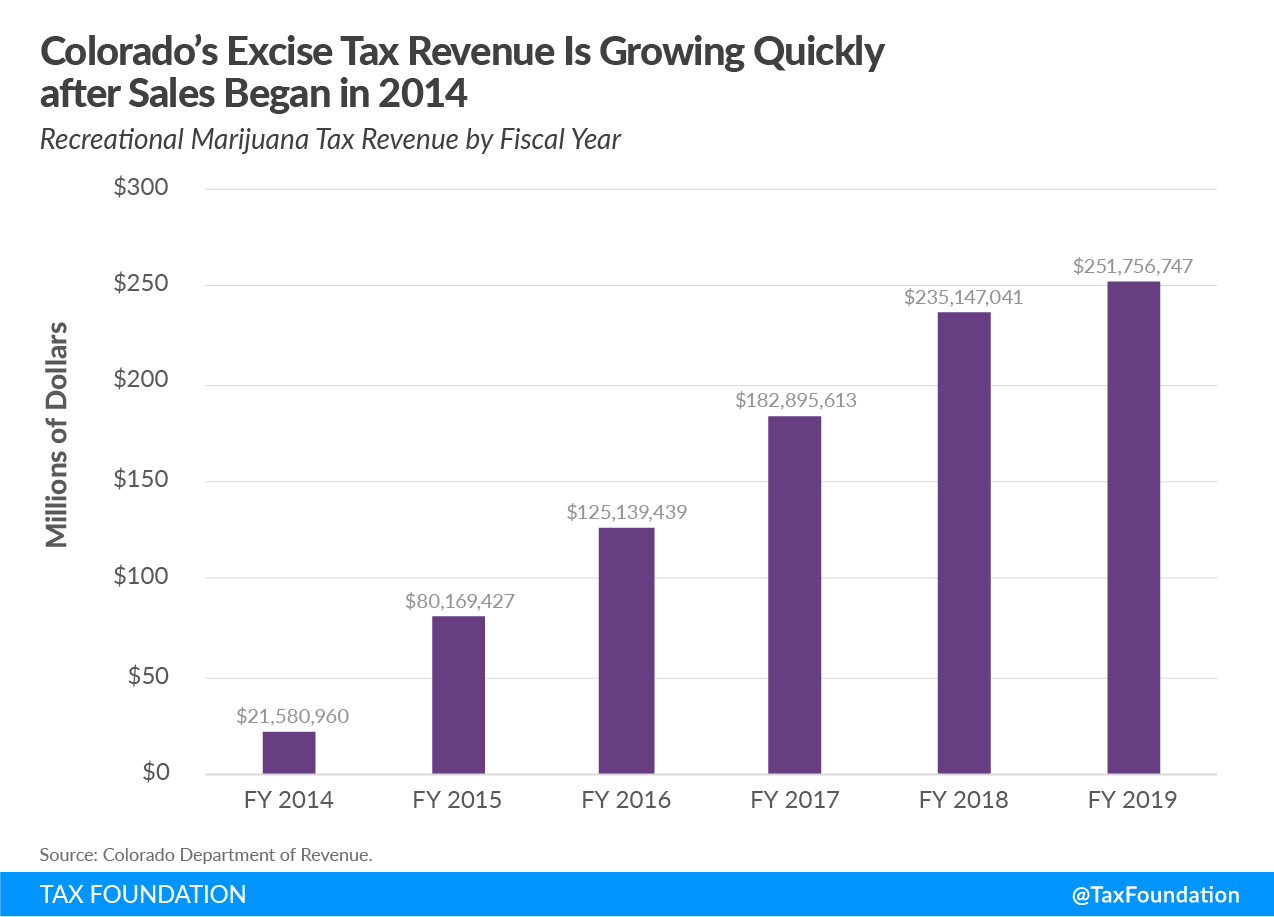

Colorado was the first state to launch a legal recreational marijuana market and is thus the best resource for “long-term” lessons. Retail marijuana sales in Colorado began on January 1, 2014, after voters approved Amendment 64 legalizing marijuana in November 2012 (55 percent to 45 percent) and Proposition AA establishing marijuana taxes in November 2013 (65 percent to 35 percent).[36]

Colorado adjusted its tax structure in 2017, which increased rates 2.1 percentage points. The original structure was a wholesale excise tax of 15 percent, a retail excise tax of 10 percent, and a general sales tax of 2.9 percent. This was changed to a 15 percent wholesale excise tax and a 15 percent retail excise tax, while exempting recreational marijuana from the general sales tax.

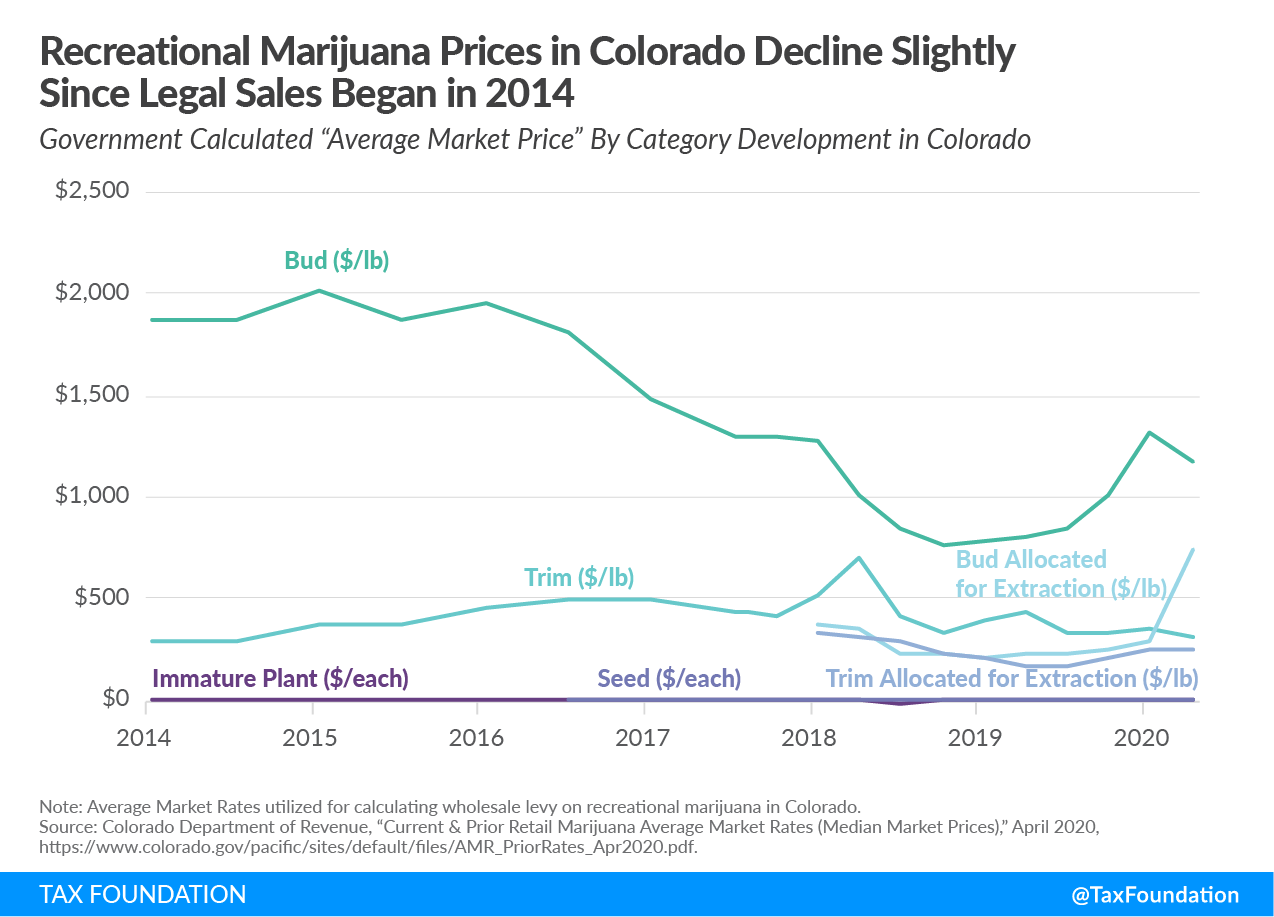

If there is no contract price and the transfer meets four criteria, or if marijuana is moved within vertically integrated companies (companies that operate both as wholesalers and retailers), the wholesale tax is levied based on an Average Market Rate per pound established by the Department of Revenue, updated quarterly.[37] That means the state technically taxes wholesalers based on weight rather than on value—with quarterly adjusted rates. This allows for easier forecasting of revenues on a quarterly basis and limits some risks of volatility associated with ad valorem taxation.

In 2018, Marijuana Policy Group was commissioned by the Colorado Department of Revenue to assess market size and demand.[38] According to the report, 302 metric tons of flower-equivalent product were sold in 2017 in Colorado.[39] Based on an estimate of adult demand (209 tons), the report concludes that the illicit market in Colorado has been absorbed by legal operations.[40] While it could seem that illegal consumption of marijuana is at least rare, if not gone, in Colorado, the state still struggles with illicit operations—particularly as an exporter.[41] According to the Colorado Division of Criminal Justice, organized drug crime increased from 2015 to 2017.[42] There is, however, some hope that illegal exports would decline if more states legalized consumption.

Revenue collected from the wholesale level excise tax is appropriated to provide $40 million to public school construction, with additional revenue to the public school fund. Revenue from the retail level excise tax goes to the general fund, to the Department of Education, and to the Marijuana Tax Cash Fund. The Tax Cash Fund funds a number of government programs.

Tax revenue grew quickly in the first years after legalization—outpacing projections made by state forecasters—but growth has slowed as the market matured.[43] Nonetheless, Colorado is on track for more growth in FY 2020.

In May 2019, the Illinois legislature passed the Illinois Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act, becoming the first state to legalize marijuana sales through the legislature. Sales began January 1, 2020 and in the first quarter of 2020, dispensaries sold almost $110 million worth of recreational marijuana.[44]

Illinois is the only state that includes potency in its tax design. At the wholesale level, the state levies a 7 percent tax on the value of the product. At the retail level, the rates are 10 percent of value if the marijuana product contains less than 35 percent of THC, 25 percent on products containing more than 35 percent of THC, and 20 percent on infused products (not intended for smoking). Additionally, the state levies the general sales tax and allows localities to levy additional tax up to 3 percent.[45]

While the first quarter of sales was successful, Illinois’ high tax rates and cap of licenses could limit growth compared to the experiences of other states.

Illinois estimated revenue totaling $28 million in FY 2020 and $127 million in FY 2021.[46] Of the collected revenue, 35 percent goes to the general fund, 25 percent to Illinois’ Recover, Reinvest and Renew Program, 20 percent to mental health services and substance abuse, 10 percent to pay state bills, 8 percent to local government, and 2 percent to public education.

Maine voters approved Question 1 on November 8, 2016, legalizing recreational marijuana. Question 1 includes a provision to levy a 10 percent sales tax on recreational marijuana and stipulates that this is the only tax to be levied on the sale of marijuana. The levy was estimated to raise $2.8 million in the first six months after sales began, and $10.7 million in subsequent years. The tax revenue is to be allocated to the general fund (98 percent) and local governments (2 percent).[47]

Though originally intended to start in 2018, there is still no operational market in the state of Maine. In 2017, Governor Paul LePage (R) vetoed a bill (LD 1719) to regulate and tax marijuana, which the legislature later overrode, but the process postponed the launch. Since then, the legislature has passed the final rules for regulation and taxation, and the Office of Marijuana Policy has begun to issue licenses.

In the final rules a few changes were made to the original bill passed by the voters. While the excise tax of 10 percent of retail sales remains, a number of taxes will be levied on cultivation. Mature plants and flower will be taxed at $335 per pound and trim at $94 per pound, plus $1.50 per seedling or immature plant and $0.30 per seed.[48] Revenue from both the cultivation excise tax and the retail excise tax will be allocated to the general fund, except for 12 percent, which will go to the Adult Use Marijuana Public Health and Safety Fund. The fund will pay for educational programs related to the use of marijuana as well as law enforcement operations related to the use and sale of marijuana.[49]

Sales were recently scheduled to begin in the first half of 2020, but the coronavirus pandemic postponed this timeline. The current timeline remains unknown.

Voters in Massachusetts approved Ballot Question 4 on Election Day in 2016, legalizing recreational marijuana, with sales beginning in November 2018. Massachusetts taxes recreational marijuana ad valorem through a retail excise tax of 10.75 percent. In addition, sales are taxed through the general sales tax of 6.25 percent and a local option up to 3 percent.[50] Shops reported sales worth $420 million in calendar year 2019, which, at a rate of 10.75 percent excise tax, would put revenues at approximately $40 million.[51] The state collected $22 million in FY 2019, which only reflects eight months of sale, but has budgeted tax revenue of $132.5 million for FY 2020.[52] About one-third of Massachusetts’ towns ban marijuana operations.[53]

The tax was originally estimated to raise between $44 million and $82 million in FY 2019. Revenue collected through the excise tax is allocated to the Marijuana Revenue Fund. After covering expenses related to running the system ($13.4 million in FY 2020), money will be spent on substance abuse prevention, awareness campaigns, public safety, and youth education programs. Furthermore, the revenue is supposed to help communities particularly affected by marijuana prohibition.[54] The distribution requirement in the law is vague, and the Massachusetts legislature has been criticized for only allocating money to public health so far.[55]

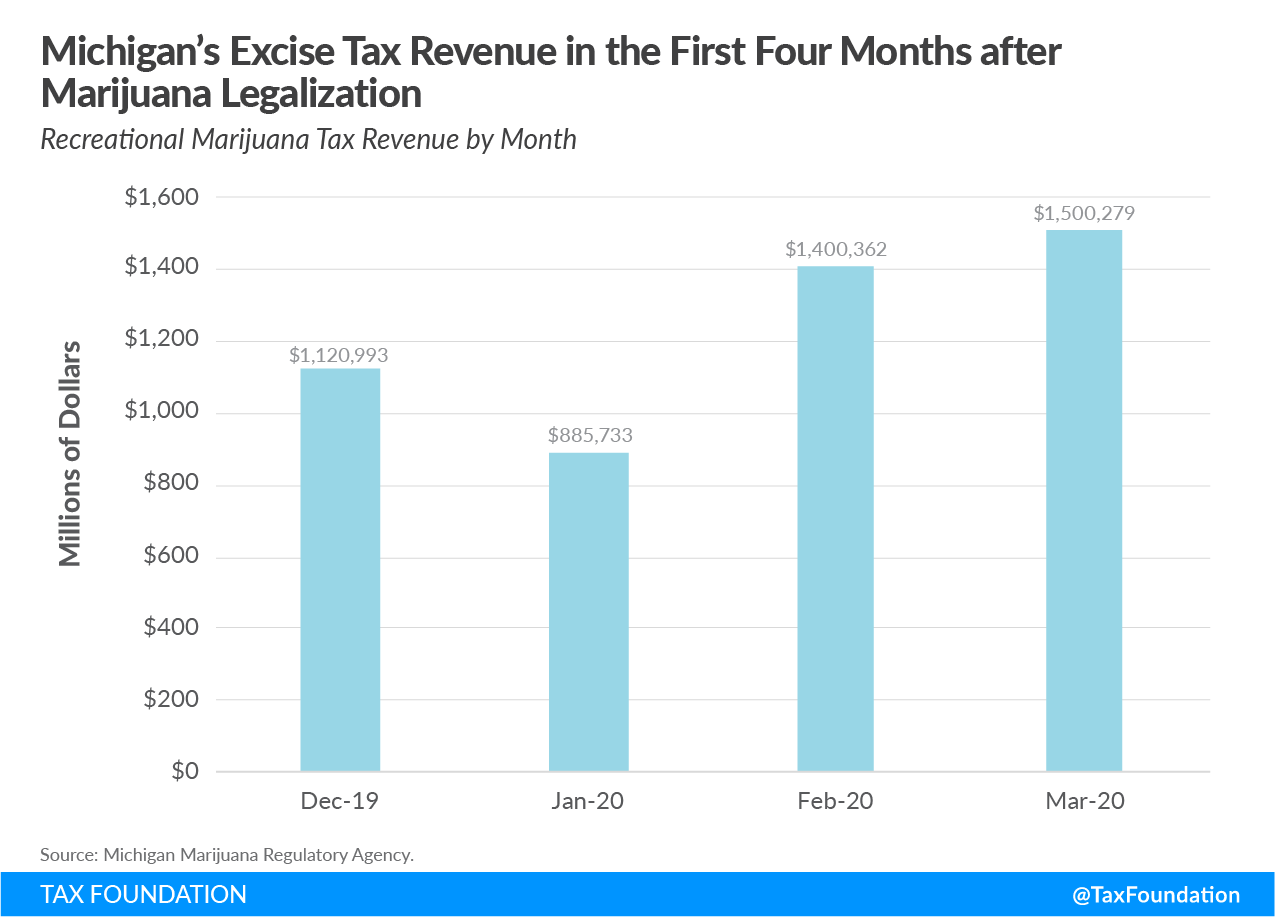

Voters approved legalization with Ballot Proposal 1 in November 2018 (56 percent to 44 percent). Sales began in December 2019.

Michigan has the lowest rate of taxation nationwide with a 10 percent excise tax on retail sales and the general sales tax of 6 percent.[56] In the first two months of sale, Michigan dispensaries sold marijuana worth almost $18 million. According to state estimates, marijuana sales could generate between $125 million and $150 million by FY 2022, when the market is fully operational. The fiscal note produced by the Michigan’s House Fiscal Agency acknowledges that unknown price developments make these estimates highly uncertain.[57] There are early signs that this worry may be well-founded: Since sales launched in December, the median retail price of marijuana flower has declined $50, almost a 10 percent drop.[58]

The revenue will first be distributed to medical marijuana research ($20 million in the first two years), with the remainder split among cities, townships, and villages; counties; the state’s School Aid Fund; and the Michigan Transportation Fund.[59]

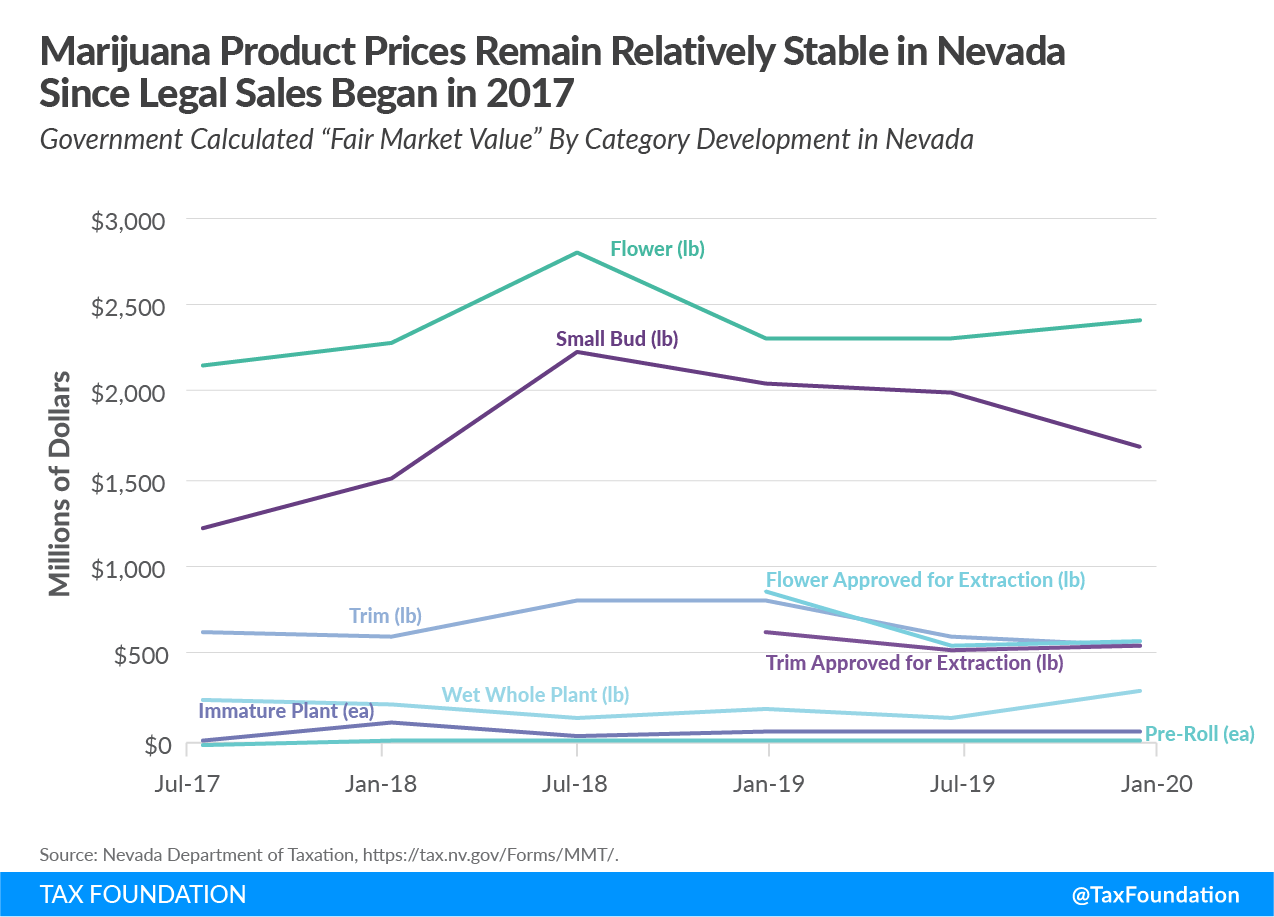

Question 2 was approved by Nevada voters in November 2016 (54 percent to 46 percent), with sales beginning in July 2017. The ballot initiative stipulated that the state should, in addition to sales taxes, tax recreational marijuana at a rate of 15 percent of the Fair Market Value at wholesale level.[60] The Fair Market Value is based on mean price of different categories in the preceding months and is updated every six months. At the retail level, sales are taxed at a rate of 10 percent.[61]

Revenue from the wholesale tax is allocated to Nevada schools after covering expenses to run the system. Revenue from the retail tax is allocated to the state’s rainy day fund.[62]

By taxing wholesale marijuana based on the Fair Market Value, Nevada is less exposed to sudden price developments that would result in tax revenue volatility. It also eliminates the valuation problem for vertically integrated companies, which, in an ad valorem system, would have to compute the taxable value in the absence of a transaction and contract price.

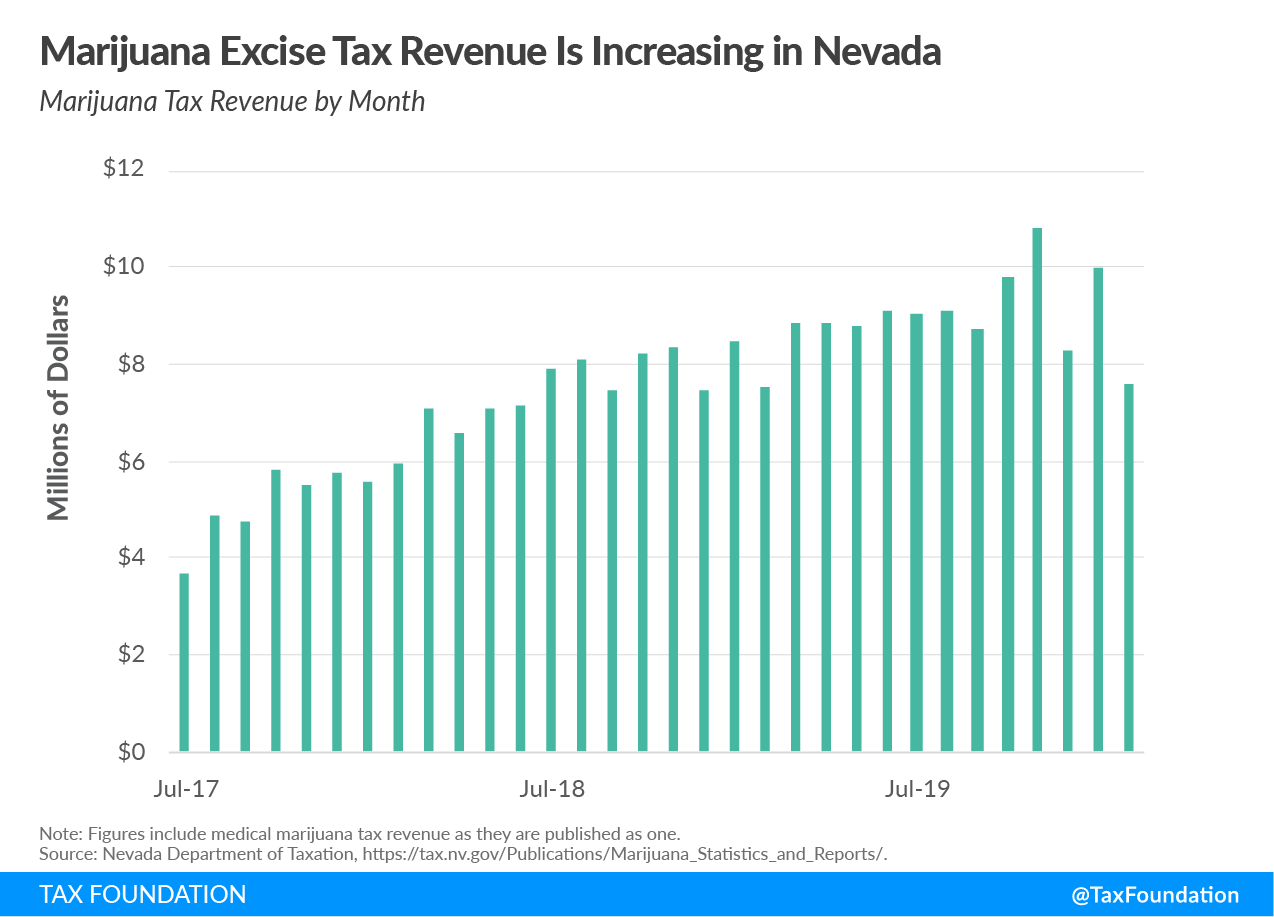

In the fiscal year (FY 2018) after legalization Nevada collected $69.8 million in marijuana taxes—140 percent of the forecasted amount. The revenue from the wholesale tax totaled $27.3 million and includes revenue from both recreational and medical marijuana, which are both taxed at 15 percent. The 10 percent retail excise tax raised $42.5 million.[63] These figures grew to $44 million for the wholesale tax and $55 million for the retail tax in FY 2019, beating estimates by $30 million for the fiscal year.[64]

Recreational marijuana sales began on October 1, 2015, after voters approved Measure 91 legalizing marijuana in November 2014 (56 percent to 44 percent). Sales were originally scheduled to start in the fall of 2016, but legislation allowing existing medical marijuana facilities to sell to all adults was approved in July 2015 in the hopes of minimizing the black market. Marijuana possession also became legal in July 2015.[65]

Measure 91 stipulated a harvest tax to be imposed on growers at $35 per ounce of marijuana flower, $10 per ounce of leaves, and $5 per immature plant. The tax revenue would be distributed 40 percent to schools, 20 percent to mental health alcoholism and drug services, 15 percent to the state police, 10 percent to cities, 10 percent to counties, and 5 percent to the Oregon Health Authority.[66]

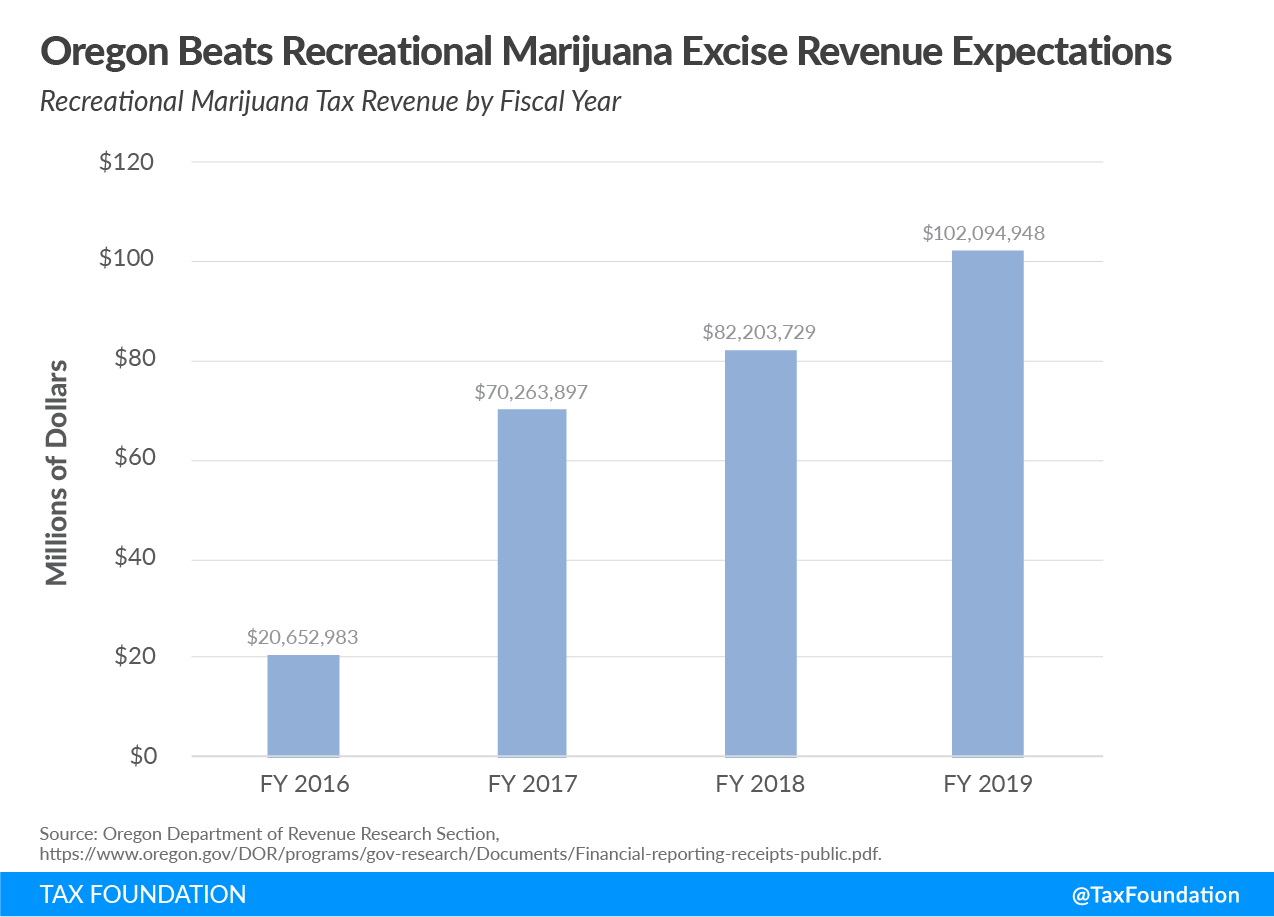

In an effort to lighten the burden on the industry and to simplify the levy on edibles and other products, legislators replaced the weight-based system with a 17 percent tax on the retail price of recreational marijuana.[67] Localities can impose an additional 3 percent tax.[68] The Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC), which is involved in tax administration, anticipated revenue of $18 million in the 2015-2017 biennium, and $142 million in the 2017-2019 biennium.[69] Oregon exceeded the initial projections as it collected $20.7 million in FY16, $70 million in FY2017, $82 million in FY2018, and $102 million in FY2019.[70]

While Oregon has managed to increase its receipts year over year, the figures hide the impact of declining prices. The increase in quantities sold masked the big price decreases’ effect on tax per product between 2018 and 2019. Of course, that effect also works the other way when prices increase, as they did through the second half of 2019. In the end, the likely decline in prices over time may hurt Oregon’s ability to continue to grow excise revenue with an ad valorem tax.

Oregon has been successful in enticing a large number of illicit or loosely regulated growers to enter the legal market. This is largely as a result of incentives (low fees and no cap on licenses) for many growers to leave the gray/black market.[71]

However, according to a 2019 study by the OLCC, the production of marijuana was twice as big as the demand in the state. A long history of marijuana production in Oregon means that it has not had to create a new industry, but rather convert an existing one. The same report concludes that Oregon is winning the battle over the black market as there is little reason to consume illegally sourced products. But that success comes with its own problems because a large oversupply means there is likely to be a lot of marijuana illegally diverted to other states.[72] In fact, neighboring Idaho has experienced a 665 percent increase in seizures of illicit marijuana between 2016 and 2018.[73]

In 2014, Vermont commissioned a RAND Corporation study that estimated that Vermont could raise between $20 million and $75 million in tax revenue a year from marijuana legalization, but also cautioned that these figures were highly uncertain and could be affected by federal regulation or neighboring states offering lower rates on marijuana.[74]

In January 2018, Vermont’s House and Senate passed a bill (H511) that legalized recreational marijuana for adults. The bill did not include any provisions about legal sale or cultivation. But there continues to be support among lawmakers to establish a regulated market as the state currently allows consumption without offering a regulated marketplace.

In February 2020, the Senate passed a bill (S54) that will establish a market for marijuana in 2022. The House passed the same bill, with amendments. Before eventually heading to Gov. Phil Scott (R), the chambers will have to work out a few disagreements within the proposals. For instance, the House is proposing an excise rate of 14 percent of retail value (excluding a 6 percent sales tax) where the Senate is proposing a 16 percent rate and a local option of 2 percent.[75] Notably, the Senate proposal would also ban flower with more than 30 percent of THC and solids containing more than 60 percent of THC.[76] That would make Vermont the only state to ban products exceeding certain THC levels.

The bill allocated the money to educational programs. A 16 percent rate is projected to raise between $8.6 million and $16.6 million from FY 2024.[77]

Washington was the second state to launch sales. Recreational marijuana sales in Washington began on July 8, 2014, after voters approved Initiative 502 in November 2012 (56 percent to 44 percent). Medical marijuana had been legal in the state since the passage of Initiative 692 in 1998, and that industry had effectively no state licensing requirements, production standards, agricultural or health regulations, or taxation beyond the regular sales tax. Having separate and parallel medical marijuana and recreational marijuana systems proved unworkable, so medical and recreational marijuana are now under a harmonized and merged regulatory framework.[78]

In July 2015, Washington changed its excise tax structure from a tiered system: 25 percent on the value of grower sales to processors, another 25 percent on processors to retailers, and 25 percent on retail sales. It is now a 37 percent tax on retail sales. The original system encouraged vertically integrated operations and caused tax pyramiding Tax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. for unassociated businesses.[79] Washington also thought the system created an avoidable federal tax burden.[80]

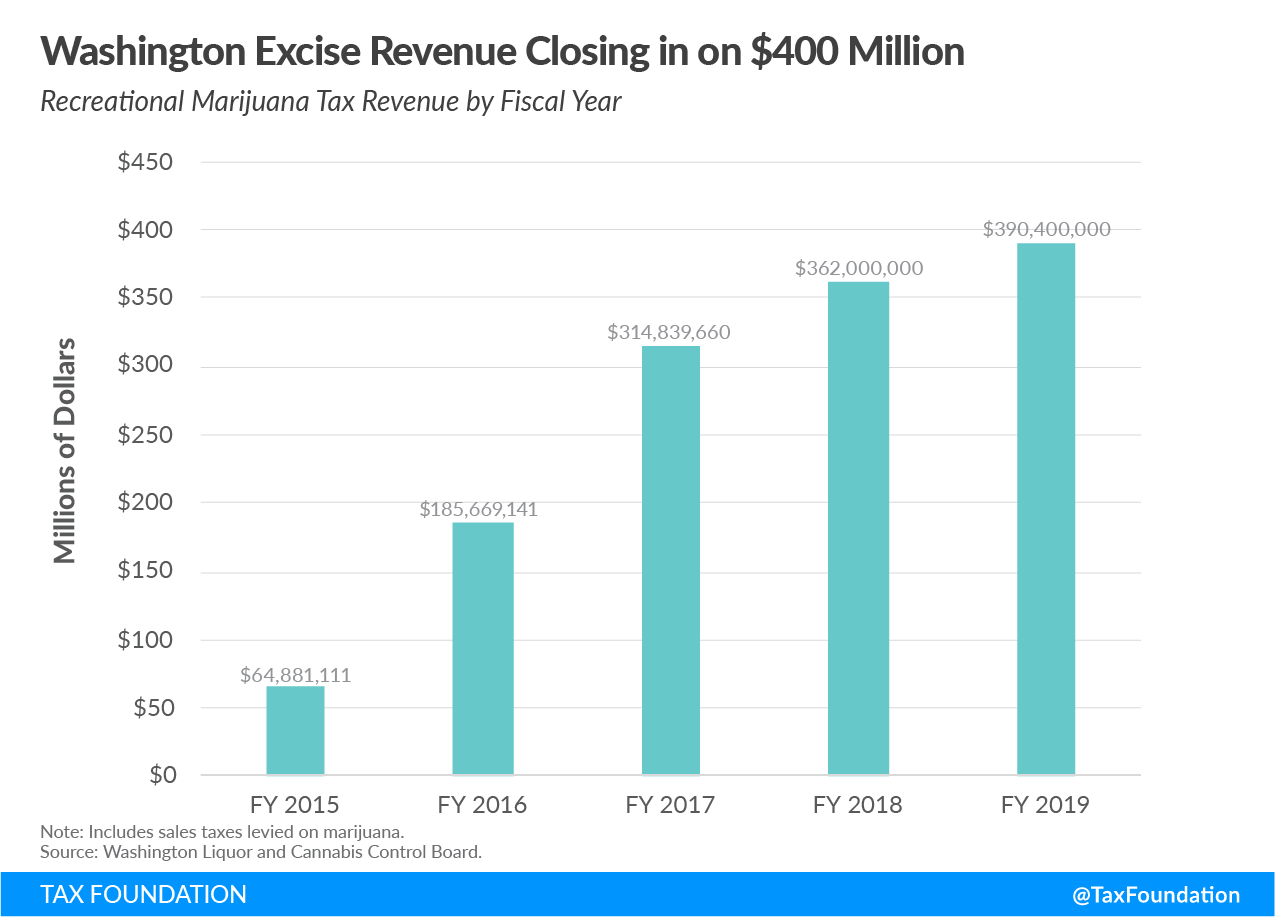

Voters were told legalization could raise up to $1.9 billion over five years, with 40 percent going to the state general fund and local budgets and the remaining 60 percent intended for substance abuse prevention, research, education, and health care. In its first full year of sales, from July 1, 2015 to June 30, 2016, Washington state collected $64.9 million. Excise tax collection estimates for FY 2016 were $134 million. While retail sales started very slowly in 2014, monthly sales grew from $7 million in October 2014 to $35 million in October 2015.[81]

The state did not manage to raise $1.9 billion in the first five years, but has, according to one study, been successful in converting many users into the legal market.[82] The relatively high tax rate and success in converting users may explain why, according to our revenue estimates, Washington State has been the most successful state in the country in terms of collecting excise revenue per marijuana users in the state.

As a revenue tool, excise taxes are worse than broad-based taxes like income taxes or sales taxes. However, as a means to recover some societal costs caused by marijuana consumption or to fund related programs, excise taxes can play a role. The idea is that the retail cost the consumer pays (exclusive of excise taxes) does not reflect the actual cost of the commodity because consumption imposes costs on others. An excise tax levy can make up the difference and recover some of the cost to society.

In order to tax marijuana efficiently, the tax should be levied at a rate that corresponds to the external cost associated with the product. This is difficult as the actual external cost is hard to estimate for any product, and no study on the subject exists for marijuana.[83] Not only is it hard to estimate cost related to marijuana use, but external cost is also impacted by substitution. For instance, the external cost of marijuana use is smaller if consumption of marijuana is substituted for alcohol, painkillers, or tobacco consumption and vice versa. Nonetheless, these principles can be helpful to tax writers.

The legalization of marijuana is an attempt to move illegal trade into a legal marketplace—much like what happened in the early years after the end of Prohibition. In 1933, during a hearing in the House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, lawmakers discussed taxation levels of liquor in the post-Prohibition era. They concluded that a “drastic price competition by the legal industry will be necessary in the earlier post-Prohibition period while the illegal industry is still organized and well financed.”[84] However, it was also concluded that price parity between illegal and legal products would result in the gradual decline of illegal products, as it did.[85] The efforts following Prohibition proved successful, as the tax revenue grew from 2 percent of total federal receipts in 1933 to 13 percent of total federal receipts by 1936.[86]

As marijuana legalization efforts continue, lawmakers are faced with a similar situation, and can draw lessons from the successful post-Prohibition strategies. It is now, as it was then, important to raise sufficient revenue from excise taxes to fund related spending while ensuring that legal sellers can outcompete illicit operators. Excise taxes on marijuana should not, however, be a measure to raise general fund revenue.

The strategy of facilitating affordable accessible marijuana seems to have worked in Colorado, Oregon, and Washington, where legal sales have successfully outcompeted the illicit market—at least to a certain degree. At the same time, the states have raised the revenue required to cover the cost of the system.

Based on the experiences from the states already allowing sales of recreational marijuana, some key lessons can be identified:

Before the discussion of tax design, there are a few important elements of legalization to introduce: illicit sales, home growing, and the impact from federal regulation.

Successfully outcompeting illicit market sales obviously makes a massive difference to the revenue states can expect. Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a one-size-fits-all solution to this as there are significant differences in the illicit markets among states. In some markets, like California, Oregon, and Washington, an established and culturally accepted, yet unlicensed, marijuana industry has been operating relatively openly. In Illinois and Nevada, illicit sales have had a more back alley nature. It is important for policymakers to be familiar with the illicit market when setting tax rates. The makeup of the illicit operations impacts the price of illicit product as it impacts the prohibition premium—the price sellers charge due to the illegality of the transaction.

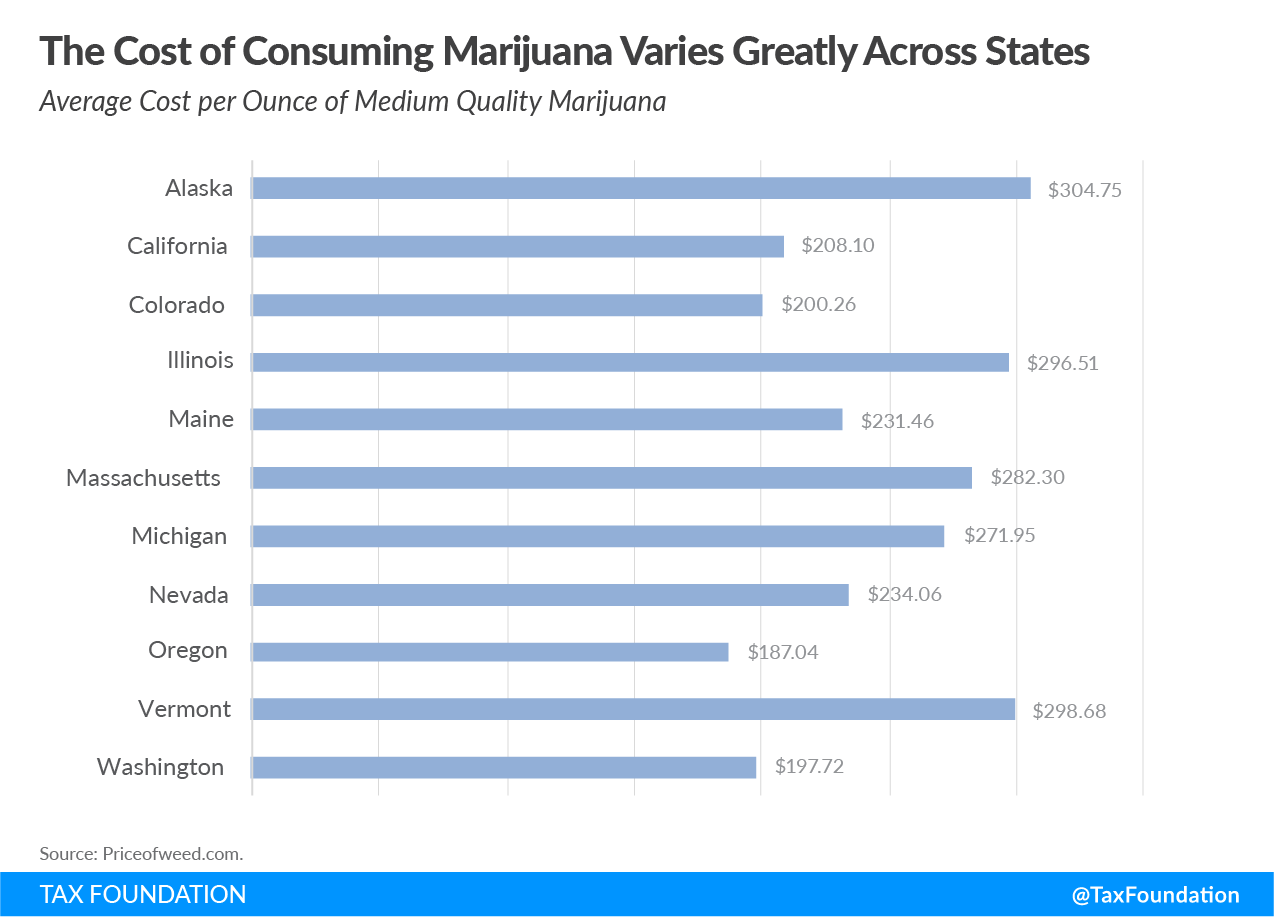

According to an unofficial global price index, the price for marijuana flower, the main product on the illicit market, differs state by state but averages approximately $280 per ounce nationally.[87] Flower also has the greatest price elasticity due to illicit market availability.

This difference in price levels among states impacts the excise tax rates if the strategy is to convert users from the illicit markets. Moreover, it is not just local prices that lawmakers will have to monitor. Marijuana flows, like cigarettes, from lower-priced markets to higher-priced markets.

The provisions surrounding home growing can also affect the market for marijuana. Nine of the 11 states that have legalized recreational marijuana allow tax-free home growing, with most states limiting the amount of plants that people can cultivate at home. In Alaska, California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Oregon, and Vermont, residents older than 21 can grow marijuana. The good news is that states that allow home grow have not experienced dramatic effects on revenue.[88]

There are a few reasons why states may allow home grow. Where localities have the option to ban marijuana sales, home grow can help the effort to eliminate the illicit market. In Nevada, residents are permitted to cultivate marijuana if they reside further than 25 miles away from the nearest dispensary. For medical marijuana users, it can dramatically cut costs, as medical marijuana is not covered by insurance.

One question that lawmakers will have to answer is whether to allow home cultivated product to enter the licensed marketplace. Depending on point of taxation, allowing this can make enforcement of health and safety regulation and tax collection more difficult. An experienced grower can get up to 36 ounces out of one plant.[89] When compared with an estimated annual use of 20.5 ounces for heavy users, it could be advisable to limit home cultivation to home consumption.

Changes to federal law would have massive implications for the tax base The tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. in any state with legalized marijuana. If businesses had easier access to banking, federal tax deductions, and across-state border business, prices would most likely fall significantly. Federal taxes could also change the picture.[90]

Tax law is a major federal obstacle to state efforts to allow a legal marijuana industry: 26 U.S.C. § 280E singles out legal marijuana retailers for a significantly higher income tax burden relative to other types of legal businesses. All businesses, including illegal businesses, are required to pay income tax on the difference between their revenue and their expenses, and marijuana businesses are not allowed to deduct common business expenses (except for cost of goods sold).

Section 280E was enacted in 1982 to deny the deduction of business expenses to those selling drugs on Schedules I and II of the Controlled Substances Act. While intended to stop illicit sellers from deducting expenses like guns and yachts used in smuggling operations, the IRS applies it to state-authorized marijuana retailers, punishing taxpayers trying to comply with the law and creating a competitive advantage for the illicit operators that Section 280E was enacted to penalize.

Were marijuana to be legalized at the federal level without a subsequent federal tax, compliant marijuana businesses would get an effective tax cut. Tax cuts as a result of legalization seem unlikely, and repeal of 280E was estimated in 2017 to lower federal receipts as much as $5 billion over 10 years according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT).[91] Thus, a federal legalization would likely include a tax to, at the minimum, raise more revenue than the change to 280E would cost. It should be included in any assessment of 280E that a repeal (and normal access to banking) is likely to increase taxpayer compliance by existing companies. A report from the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration found significant compliance issues and underreporting of income under the current system.[92]

A federal tax should, like a well-designed state tax, seek to tax the externality and avoid distorting the legal market. Any federal tax would impact price level and compliance costs in the states, and lawmakers at all levels of government should stay attentive to the interplay between federal taxes and state and local taxes.

One element of federal legalization may impact taxation revenues indirectly by limiting access to medical marijuana regulation. It is likely that the Food and Drug Administration would issue stricter guidelines for issuing prescriptions for medical marijuana. Currently, doctors issue recommendations rather than prescriptions because marijuana is a schedule 1 controlled substance. Limited access to medical marijuana would limit the risk of the medical marijuana becoming a tax avoidance scheme.

Lawmakers designing excise taxes for recreational marijuana will have to balance two opposing consequences of tax rates. High rates may limit adoption by minors and current non-users but may also impair competitiveness of the legal market. Low rates may beat the illicit market more easily but could also increase consumption among current non-users and minors. Whichever goal is more important to lawmakers, the rate should enable the state to collect enough revenue to cover the cost of funding marijuana-related programs.

Separate from the rate, choice of tax base can affect product development. For instance, taxing by price could drive down prices as consumers and businesses look to lower their tax liability. Taxing based on weight could encourage use of high potency products. Taxing based on THC content could complicate tax collection and add significant costs to both tax collectors and industry.

An excise tax should be based on the following principles:

Most states have implemented price-based (ad valorem) taxes on recreational marijuana levied at the retail level. This is likely due to the simplicity associated with establishing an ad valorem system. Taxing based on retail prices means there is a taxable event with a transaction allowing for simple valuation. However, if applied at the wholesale level, vertically integrated businesses can have trouble calculating the value as there is no transaction. To offset that, Colorado and Nevada levy their ad valorem tax based on a fixed rate (adjusted at different intervals) and weight, which means, although structured as an ad valorem tax, applying a fixed price essentially converts these taxes to a weight-based tax.

Conversely, taxing based on weight or potency adds complexity given the wide variety of products available. Yet, while it may be simpler to levy the tax based on price, it does not necessarily offer an equitable solution. A marijuana product with similar qualities and in similar quantities should have equal tax liability regardless of design or price, but this principle is ignored by an ad valorem tax design. Taxation should be aimed at the externality, which is best expressed by the THC level. While price could technically act as a proxy for the strength of the products, it is far from a perfect solution.

Furthermore, taxing based on the price harms consumer choice and product quality as it incentivizes manufacturers and retailers to reduce prices to limit tax liability. It also incentivizes downtrading, which is when consumers move from premium products to cheaper alternatives. Downtrading effects do not reduce harm and have no relation to any externality the tax is seeking to capture.

Often, ad valorem taxes also result in tax pyramiding, which is when a state levies an excise tax at the wholesale level and a retail tax based on retail selling price. The wholesale tax is built into the retail selling price on which the retail tax is based, resulting in a tax on a tax. This issue is not unique to marijuana taxation but is important considering a potential multiplier effect in states with high taxes if a federal tax is implemented before retail.

Like any tax in an immature market, ad valorem systems run the risk of being too high in the beginning, where supply is low, and too high after a few years, when prices might drop significantly. When supply is low, the tax rate may add significant cost to an already scarce expensive product. As the market develops, prices may fall, which would subsequently reduce tax revenue. This effect is not yet widely noticed as states have been expanding the market, with growth in sales masking this effect. Nonetheless, the longevity of an ad valorem system remains uncertain as, according to a report from the Congressional Research Service, the price per ounce may fall as low as $15-$18.[93]

Ad valorem systems are also susceptible to tax avoidance schemes, where consumers can get “free” marijuana if they buy a T-shirt, pay a cover fee to enter an establishment, or donate a certain amount. They can also result in tax cuts for discounts unrelated to externalities, like standard commercial quantity and employee discounts. Lawmakers should be aware of this when writing the law.

Consequently, ad valorem taxes offer a simple and quick option for states but may create issues down the road as market develops and prices decline (especially in the case of federal legalization that could open the door for interstate marijuana commerce). Moreover, these taxes do not tax products equitably and are vulnerable to distortion from potential federal taxes. States that implement ad valorem taxes should stay attentive to developments that may affect their market and revenue in the short term.

Specific taxes based on quantity are the most commonly applied excise taxes. Such taxes are currently applied to spirits (volume-based), cigarettes (per stick), and motor fuel (volume-based). It could thus seem straightforward to apply a simple weight-based tax (e.g., per ounce) on marijuana as well.

One of the reasons that specific taxes can be advantageous is that they generally are more stable because they are not affected by changes in consumer brand preference or retail prices. In regard to marijuana taxes, specific taxes would not be exposed to potential declining prices as they remain fixed regardless of price developments. They may even offset price declines as specific taxes can act as a tool to establish a minimum retail selling price. Combined, that means it would be easier for governments to forecast revenue.

What weight-based taxes offer in stability, they lack in simplicity. Taxing based on weight introduces greater complexity to the system. For instance, multiple weight categories must be defined as the weight of trim cannot be compared to the weight of flower, and so on—requiring a system such as that used in both alcohol (beer versus liquor) and tobacco taxation (cigars versus cigarettes). Additionally, fresh flower weighs more than dried flower, and techniques such as flash freezing further complicate the system.[94]

As an example, Colorado, which has a de facto weight-based tax at the wholesale level, operates with seven categories for weight:

Along with well-defined categories, lawmakers must also define when to weigh the product and who is responsible for collecting and remitting. States operating with weight-based systems would likely have to collect taxes early in the value chain before the marijuana is processed and packaged as concentrates or edibles.

In one way, weight-based taxes are simpler than ad valorem. For vertically integrated companies, weight-based taxes do not require artificial valuation. Nevada and Colorado have solved this by levying the wholesale ad valorem tax based on a temporarily fixed value per ounce.

While weight-based taxes could be more equitable than ad valorem, they would likely favor high-potency products. For instance, highly potent flower weighs the same as a less potent flower. Further, the system does not consider the ability to extract THC from the flower and create highly potent concentrates from a small amount of plant material. With alcohol taxes this issue is solved by taxing products based on both volume and potency (defined by alcohol content). States taxing different parts of the marijuana plant at different rates offsets some of this issue but does not manage to capture the externality down the value chain. As opposed to weight-based taxes on alcohol and tobacco which are levied on the final product rather than on the ingredient, existing weight-based taxes on marijuana are levied on the plant material, which may or may not be the final product.

Finally, to ensure that a weight-based tax system is not eroded by inflation, a low-rate, weight-based tax should be indexed to automatically reflect inflation.

It is normally a virtue to keep taxes as simple as possible, but in this case focusing on simplicity alone would result in an unequitable and nonneutral tax. Relying on potency as a tax base introduces complexity to the system but also allows the excise tax to do what it is supposed to do—that is, to capture the negative externality.

In 2019, the Washington State Liquor & Cannabis Board published a report on the feasibility of implementing a potency-based tax in Washington. The report finds that the lack of available data makes it difficult to draw solid conclusions but suggests that a potency-based tax may encourage consumers to move to less potent products.[96] Also in 2019, in California, the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) published a report recommending changing the existing taxes to a potency-based system. LAO recommends a rate between $0.006 and $0.009 per milligram of THC.[97]

Taxing recreational marijuana based on THC content could be the most equitable design because it most directly captures the externality associated with consumption—that is, if THC is truly a proxy for potency. Some suggest that other cannabinoids play a significant role in determining potency of the product.[98]

Under a THC-based tax system, more potent products will be more expensive, reflecting the additional cost related to higher THC consumption. This would not be groundbreaking in tax policy as potency is a well-established proxy for tax bases in the United States. Alcohol products are taxed in categories based on their potency.

Illinois has implemented a system that incorporates elements of a potency-based tax while still relying on price to determine taxable value, the first state to do so. While Illinois’ system does reflect the relative difference in harm as it relates to THC content, it remains exposed to the shortfalls of an ad valorem tax.

At this point, the main issue with implementing a potency-based tax is reliable testing, specifically for raw plant material. This is no small issue as there may be significant problems developing tests that reliably measure the THC level consistently. The marijuana industry is a young industry and currently test results depend on which lab tests the product. While there are some testing standards developed for labs, it is paramount that businesses and tax collectors alike can trust test results if tax liability is to be determined by those.[99]

One way that lawmakers may make the system workable now is to combine weight-based taxes and potency-based taxes. By introducing THC intervals in a similar style to alcohol intervals, testing may be easier as the acceptable margin of error is larger. This could be done by taxing the plant materials according to weight, but at different rates according to THC content. As an example, plant material with less than 20 percent THC could be taxed at rate X while plant material with more than 20 percent THC would be taxed at rate Y.[100] This design could offset some of the issues related to relying on weight-based taxation while respecting the fact that quantity of smokable plant also plays a role in determining the externality. Applying taxes by THC intervals introduces tax cliffs which could distort the market.[101] Nonetheless, it would still be the most equitable and realistic option at this point.

Using THC ranges to calculate tax liability accounts for this. Furthermore, when designing tax policy targeted externalities, it is important to consider different delivery methods. For instance, THC delivered by smoking yields a lower amount of THC as much is destroyed by the combustion. THC delivered in edibles does not incur any combustion and a larger percentage of the THC in the product reaches the body. According to a report prepared for the Colorado Department of Revenue the ratio is around one to five.[102]

That is not to say that smoking marijuana is necessarily less harmful as smoking marijuana creates additional externalities like carcinogens from combustion. Nonetheless, these factors suggest a need for different rates for different delivery methods, a system already used in Canada.[103] Such a system similarly already exists for nicotine products, where cigarettes are the most harmful and are generally taxed at a higher rate. Adding the fact that it is easier to test edibles and concentrates, it would be natural to tax those products at a rate Z per milligram of THC.

Other complexities are related to how cannabis smokers consume marijuana. It is possible that smoking marijuana with low potency either changes inhalation patterns or encourages additional consumption length to achieve a certain THC level.[104] While a weight component of a potency tax could offset some of these effects, this would be important to evaluate. There are also increasingly popular products which are either low- or no-THC (for instance, CBD and THCa). Depending on the externalities related to these products, these can either be taxed at the same rate as low-potency marijuana or they may require individual categories.

Besides being the most equitable option, potency-based taxes have the added benefit of encouraging consumption of less potent products over high-potency products, though the tax should not be so high as to encourage consumers to move back into the black market. As is the case with a weight-based tax, any introductory low-rate, potency-based tax should be indexed to automatically incorporate inflation.

To best tax marijuana products equitably and stably, policymakers should stay away from ad valorem taxes despite their simplicity. Using weight or potency as a base makes for a more neutral tax while providing a more stable revenue stream for governments.

Disregarding the issues surrounding testing would suggest a potency-based tax is the best short-term solution for lawmakers. The recommended design for a potency-based tax assumes that THC content is the best proxy for potency and therefore the best measure of externalities related to marijuana consumption, but this is an area that should be studied further. The number of taxation categories can be expanded or redefined as the market develops if studies find that the recommended design does not adequately target externalities.

For both a weight and a potency-based tax, it will be necessary to develop and define tax categories to ensure equitability. The tax should be levied early in the value chain similar to alcohol, gas, and tobacco taxes to limit the number of taxpayers.[105] Limiting the number of taxpayers is important because fewer taxpayers make less work for both government and industry.

State taxes should be preferably levied at the wholesale level to avoid tax pyramiding. If interstate commerce becomes legal, marijuana risks double taxation if the origin state taxes cultivation and the destination state taxes sales. Avoiding tax pyramiding would guarantee that the excise tax is a tax on consumption rather than a tax on cultivation or production.

Excise tax revenue should be appropriated to relevant spending priorities related to the consumption of marijuana. Examples include public safety, cessation programs, marijuana research, and youth drug use education.